At the age of eighty-five, Hans Jaeger finds himself a castaway among a group of survivors on a deserted island. What is my particular crime? he asks. Why have I been chosen for this fate? And so he begns his extraordinary chronicle.

It would be an understatement to say he has lived a full life. He has grown up in Nazi Germany and falls in love with Jewish girl. He fights for the Germans on two continents, watches the Reich collapse spectacularly into occupation and starvation, and marries his former governess. After the war he goes on wildflower expeditions in the Alps, finds solace among prostitutes while his wife lay in a coma, and marries a Brazilian chambermaid in order to receive a kidney from her.

By turns sardonic and tragic and surreal, Hans’s story is the story of all of the insanity, irony and horror of the modern world itself.

If there is an actual name to this island, it is unknown to us. We have chosen to call it Illyria. We’re not exactly sure where the name comes from. Some book perhaps. But it no longer matters. It has become our own—mythic and melodic-sounding. As though, if we keep calling this place Illyria, keep pretending it has some magical allure, people will want to come. Someone will come rescue us.I am not complaining, particularly. Well, maybe I am. But I probably shouldn’t be. So far fate has proven a fair enough agent. The beaches are sandy, the water clear and turquoise, the reefs plentiful. The island is wreathed in a soothing white foam. On shore there is the shade of palms and palmettos and eucalyptus. At least we think it is eucalyptus. We call it eucalyptus. Maybe it is just some kind of fancy magnolia though. Who the hell knows?

There are fruits in relative abundance—though what they are, we aren’t sure. Some are purple. Others are yellow. Some vaguely sweet, others sharp and abrasive on the roof of the mouth. There is a variety of coconut that grows in conjoined pairs to look like the buttocks of an African woman. We call this ass-fruit. When I offered some to Conrad, he said to me, “I’m not into that shit.” As though I were suggesting something perverse. As though fear of this fetish object outweighed the need for sustenance.

“What shit are you not into?” I asked.

“Ass fruit,” he said. “Ass.”

“It’s not real ass, Conrad,” I said.

“Well, it’s not a real fruit either,” he said.

“What do you think it is then?” I asked.

“A joke,” he said. “A sick joke. Like the rest of this place.”

God is playing a joke on us. That is a common theme here. It was funny the first time someone said it. Now it is just annoying, like a child saying, “knock-knock” to you over and over, more and more emphatically, as you refuse, just as emphatically, to ask, “Who’s there?”

The other common theme here is that none of it is real. We all died when the boat went down. And this is all just a dream. Conrad suggests this a couple of times a day, each time choosing a different angle, a different inflection, in a vain attempt to keep the joke fresh. If you suggest, gently, that this joke no longer strikes you as uproarious, Conrad will immediately jump into a long denial that he is joking. “I’m not fucking kidding,” he will tell you. “I really mean it. I think this is all a dream.”

Perhaps Conrad is right. Because honestly, I did not believe, until my current predicament, that deserted islands still existed. I thought these islands were all owned by former tennis pros and former tyrants, or inhabited by caricatures of primitive tribes who sell carved bamboo flutes to flabby tourists in checkered shorts.

If it is a dream, if this is my Land of Oz and I am soon to wake up, then it is curious how, from time to time, little bits of Kansas wash up upon our shores. Whenever we wander further down the beach, away from our settlement, we find Styrofoam packing peanuts, Styrofoam bowls, #3 plastic take-out containers with their familiar, triangular recycle symbols (apparently the previous owners of these containers ignored this particular environmental imperative).

The restaurant take-out containers are the most distressing. More mockery from The Almighty. More of his levity. Ha ha. We bring them back to our camp and wonder what twenty-first century foods they once held. Pad Thai or Kung Pao Chicken or Shrimp Korma. From some restaurant from the other world. Thank you, God, for delivering us this practical joke. Ha ha. You’re fucking hi-lar-ious.

In truth though, these containers have become invaluable to us. We eat out of them, wash them out at the little pool in Piss Brook, store our meager salvaged supplies in them. If there is truly one thing we should thank God for, it is those non-recycling sinners.

In our first days here, we found a means of killing a dove-like bird that is here in abundance. We creep up on it quietly, then all at once we start hurling rocks at it from all directions. It is the same low-tech technique the Iraqis used for shooting down American planes in our first Gulf War. Just throw up flak in every direction and hope something falls out of the sky. Actually that is something else that I am no longer sure is real. Gulf War I. In my current, delusive state, I am no longer clear whether it really happened, or was some very popular video game, and Gulf War II was just the long-awaited next release, with its improved graphics and better villains and four-and-a-half star rating. Perhaps, since we have been here, Gulf War III has broken out. Or been released.

But back to the doves. With the doves, this method worked once in every ten or twenty tries. Moreover, some of us were hit by rocks. Conrad compared us to a circular firing squad. And for the effort, we each got no more than a single bite of precious meat.

Frigate birds watch us from high overhead—out of range of our stone-age weapons. There are also pelicans and sandpipers along the coves. But the only other bird we have succeeded in slaughtering—a heron of some sort—tasted much like a discarded sneaker might taste. There are also lizards and little pencil-sized snakes, but thus far we have passed on these particular specialites de la region.

So much for Illyria’s fauna. Now a word or two on the topography. The interior has proven rocky, thick with vines, and difficult to penetrate. There is a single volcanic peak in the middle, which we call Mount Piss. We call it this because the streams that run down from it are of a yellowish, sepia color—piss water. This includes our drinking source, the much despised and much revered Piss Brook. It is probably just some dissolved mineral. Iron would turn it orange. Maybe zinc? Who knows. The taste is strong and unpleasant, but it is moderately cool, given our subtropical latitude. It is keeping us alive. Probably, if we could contact the civilized world, we could bottle it and sell it for its curative powers and make great mountains of money.

Our first shelter was rigged out of bamboo and palm fronds. It was set on the beach, and we soon learned there was no way to keep out the sand crabs. They came out in large numbers every evening. It would have been one thing if they scampered in from outside. But it was stranger than that. They just rose up through the floor of sand. They tunneled in, materialized among us, little uninvited sprites, climbed up out of the ground like the living dead and crawled across us as we slept.

“We’re not high enough above the water,” Cole said. “What if a storm comes up?”

“He’s just afraid of the sand crabs,” Conrad said to me, snickering.

“The first really high tide will wash us out,” Cole said, ignoring the snickers.

“He’s right,” Monique said. Although her vote meant little. She is Cole’s lover, and seemingly agrees with everything he says and does. If he becomes the de facto king of our little group of seven, which now seems likely, she will be our queen.

Our next shelter was built just above the beach, using a cliff face for one of the walls. It was roomier, and easier to close off from the creatures. It was quieter too, farther from the surf. But that was worse, in a way. Because now you heard all of the human sounds more precisely. Cole snoring. Gloria talking in her sleep. My own imperfectly muffled farts.

One night, a rain came and our new shelter was tested. At first we just felt a kind of mist, soft and cool, that had found its way through the thatch. But then it got heavier. Droplets.

There were groans. Curses. Aborted snores. Rustling.

And then it was no longer just droplets raining on us. It was the cliff itself. Mud from the cliff started slopping on us. Little shit bombs. Dripping through our roof. It was raining crap. “Fuck!” Conrad shouted. And it was an accusation, directed at Cole, who had chosen this location.

Another splat. Another curse. And then we were all up, groaning and cursing our miserable fate—surely the world’s very last castaways, on what is surely the world’s last desert island, somewhere mysteriously out of reach of our GPS-bound, cell-towered, trawler-traversed global village.

Maybe Conrad was right. God, that sadistic little prick, was playing some kind of joke on us. God was the house cat and we were his mouse and he was taunting his mouse over and over, carrying it and dropping it and picking it up again, half-swallowing it and regurgitating it and kicking it like a soccer ball, before finally disposing of it.

So it’s shitty metaphor. What can I say?

We got up in the middle of the night, abandoned the shelter, huddled together on the beach. We were sunburnt and bitten, chilled and miserable. Hungry, filthy, greasy-haired, exhausted. Tears mixed with the downpour; our pathetic, mortal cries with the thunder of heavens.

After a while the rain stopped. We sighed, calmed, leaned against one another. Relief. Then it started again. There were no more tears by then. Just silent misery. Half-sleep. Each of us with his or her own private thoughts. My thoughts were of Dawn. (I am capitalizing Dawn not as a statement about the mystical meaning of sunrise. In fact I am not referring to the sunrise at all. I am referring to one of our company, Dawn, the youngest in our party—a nineteen-year-old girl who had won my sympathy. But I am getting ahead of myself.)

When Dawn finally came (sorry, this time I am referring to the sunrise), we straggled up and pretended—as one does on a red-eye flight when the lights pop on—that we’d actually had a night’s sleep. Only there was no stewardess, no orange juice and coffee, no magical, mile-high toilet to whisk away the miserable night’s rumblings in a screaming blue swirl.

Just another day here on Illyria.

This is my question about aboriginal peoples. Did they always feel as short of sleep, as exhausted and worn out, as we always feel? Or did they find a way to sleep through all of those night sounds and crawling things, hunger pangs and gas-emitting neighbors?

Our third shelter was set on a long, flat rock, above the waves and a half-mile down the beach. It is interesting how quickly one develops a sense of home. Just moving that half-mile seemed unsettling. An unwelcome abandoning of the familiar. We filled empty ass-fruit shells with sand and carried them up to our rock to soften the floor for sleeping. And by adding more overlapping layers of thatch than we had before, by covering it with a paste made from clay and eucalyptus sap, we managed to keep dry inside. We called our new residence Versailles.

By then, the inevitable had happened. Cole was our leader. We hadn’t exactly chosen him, and he had never asserted his authority directly. It just happened.

Was he wiser than the rest of us? More generous? Had he provided for us in some impressive way? No. He possessed what Human Resources questionnaires refer to as leadership qualities. And most of us, let’s face it, are natural followers.

It started with his suggestions. We should do this. We should do that. We should set the shelter closer to the brook. The women should gather the fruit. “You!” he would say, narrowing his eyes at Andreas, “Work on finding firewood.” It was as though he had been waiting all his life to play this role, to have the chance to tell someone to gather up the firewood. And of course it was natural to direct his first order to Andreas, who had been in his employ on the yacht before it went down. And then from there it was easy to direct “suggestions” to the rest of us.

We are a pack of primates. And Cole is our alpha male. Tall, burly, handsome in a bushy-browed sort of way. Real estate developer in his previous life. Resourceful man of the jungle in our present life. Dipshit in both lives.

With his background in real estate, so he insinuated, it was only natural that he should oversee the construction of the shelters. And though the connection seemed tenuous, nobody challenged him. Conrad, who in our previous life was Cole’s cousin, despises him. For myself, I dislike him as well, but more or less indifferently. I see that he is only of average intelligence, perhaps slightly more self-centered than what might be considered average. He is lacking in irony, introspection, humor, really anything that might make one actually like him. But I am too old to worry about these things. I have seen too much of humanity—and at its very worst. Let someone else figure it out. Just tell me what you need me to do and leave me alone and don’t ask me any questions.

Our next construction project was a dove coop. Gloria, our kindly widow (yes, dear reader, it goes without saying that our group is made up of “types,” a microcosm, as it were, of humanity at large, and that one of these types, inevitably, must be our kindly old lady), had the ingenious idea of raising doves rather than just throwing rocks at them.

“Good plan,” Cole said, nodding wisely, and somehow managing, in his nod, to demonstrate the importance of his judgment. His ratification.

It was a big step for us. Our move from a hunter-gatherer society to an agrarian economy. But it was something else also. A recognition that we might be here for a while. That we had to plan for a future. And for me it was a recognition of this:

I am done running. I am here now. There is nowhere left to go.

With great effort, we caught three of these birds alive—surrounding them and dropping a heap of branches on them. We put them in our coop.

“What if they’re all the same sex?” I asked.

“I don’t think they’re all the same sex,” Cole said.

“Why not?”

“That one looks like a girl.”

“Why do you say it looks like a girl?” I asked, wondering if Cole had noticed a wiggle to its tail, a shape to its figure.

“It’s more colorful,” Cole said.

“The male birds are more colorful than the females,” I said. I am no John James Audubon, no Roger Tory Peterson, but I believe I am right in this.

“Either way,” Cole said.

We turned the birds over, looked around their tails, but could find no conclusive evidence of maleness or femaleness. Then one morning Conrad called us over. Two of the doves were dead. The third, the apparent victor, seemed to have been bloodied.

“Maybe they were all males,” I said.

“Or maybe with doves it’s the girls that do the fighting,” Cole said.

I was skeptical of this, caught Conrad’s eye.

“Just because the males are colorful, doesn’t mean they’re girly,” Conrad said.

“So much for doves being symbols of peace,” I said.

“Unless of course they aren’t really doves,” Dawn offered up.

We all looked at her. It was rare for Dawn to speak up among the group.

“True,” I said. Because it’s not as though Dr. Doolittle is here with us and can just ask him if they are doves. Or Crocodile Dundee. Or whomever. What we know, or think we know, about the rain forest, we have learned from the packaging on our health supplements and our beauty aids and our enviro-friendly paper towels. The TV shows that bring wild nature into our living room. Here, high in the cloud forest, the spectacled monkey is tending to her young. The little ones will need to learn much if they are to survive the harsh winter. Actually, scratch that. No harsh winters in the cloud forest. But you understand my point.

Though bloodied, the dead doves still had meat on them. We brushed off the ants and flies, washed the corpses off in the stream, put them on the barbeque spit.

In the next days, we caught more doves. This time we observed the brush they pecked at in the wild and brought them piles of it. And we separated the doves into pairs that appeared to be of opposite sex. And lo! Dove eggs started to appear. Like magic. Like Easter eggs. Like…actual…eggs!

In time, one of this second set of doves died too. This time though, apparently, it was from natural causes (strange phrase: natural causes. Because what could be more rooted in nature than being pecked to death?) But we nonetheless had eggs. And while we ate some, we left some of them alone. And one day we witnessed the miracle we had dreamed of, but never quite believed we would see—a little beak pecked through one of our eggs, pecked its way out into the world. Within a couple of weeks we had a little collection of chicks. We had done it! Our poultry farm had been born!

Again we returned to our construction. Our next project was a little shelter along a rocky outcrop, to protect us from the sun when we were fishing and crabbing. And then Cole and Monique decided they wanted to sleep in privacy. So we built a second shelter alongside Versailles that we called Fontainebleau.

“Why,” Conrad grumbled, “should we be putting all this time into another shelter just so that dirtbag and that douchebag can go at it in private?”

I wondered what you get when you mate a dirtbag and a douchebag. There must be a good punch line. Please write me if you think of one. 1 Delirium Terrace. Illyria. Earth. 02483-7676. to insure proper handling, be sure to include a self-addressed, stamped envelope. And a life raft.

“Well,” I said, “the next shelter we build after that could be for you.”

“Yeah,” Conrad said, “but it’s not like there’s anyone I’m likely to be screwing.”

“Well don’t you want to be able to pleasure yourself in private?” I asked.

Conrad looked uncomfortable at this, but said nothing.

“And won’t it be nice to be rid of them?” I asked.

Personally, I was relieved when Cole and Monique moved out. It had grown tiresome, those nights they waited until they thought everyone was asleep and then started moving and rustling, whispering and slurping. And then those guttural sounds, like a pair of native frogs. Only nobody was ever really sleeping during their nocturnal choruses. We were all just pretending we were asleep. All too uncomfortable to say anything about it. To interrupt them.

“I think it actually turns them on,” Conrad used to snarl. “They know we know they’re going at it. And they know we know they know.”

“It’s difficult,” I say.

“I’m saying something next time.”

And he did. A couple of nights later we started to hear it again. Unmistakable. Rustle. Breath. More rustling. Sighing. Frog calls.

“Hey Monique,” Conrad called. “Can I get some of that?”

Suddenly the sounds stopped. Silence. The whole shelter went silent. Pretended to sleep. Like even Monique and Cole were asleep and the only one awake was Conrad and nobody had heard anything at all—the grunting or Conrad or anything. Monique and Cole frozen in flagrante delicto. A final rustle. Monique discreetly slipping off her little pole of Cole. Then more silence. Everyone pretending sleep. Until we actually were asleep. One by one. Like in that children’s story.

Goodnight Cole.

And goodnight Pole.

And goodnight, o empty soul.

Goodnight stars.

And goodnight air.

Goodnight misery everywhere.

Two days later Cole began organizing work on Fontainebleau. He must have waited an extra day so it wouldn’t be as obvious why he was doing it—that it was related directly to Conrad’s comment. Since we were all pretending we had never heard it.

Bit by bit, Cole has seemed to be developing the island. I imagine that, if a rescue ship ever comes, while the rest of us are celebrating, weeping for joy, he is going to take them for a tour, show them all the improvements, try to sell his development for a profit.

For Conrad, the last straw was one morning when Cole put up a great big bamboo cross over our little encampment.

“It’s embarrassing,” Conrad complained, pulling me aside.

“Embarrassing before whom?” I asked.

Conrad thought about this. “What would a pilot flying over us think, looking down and seeing that?”

“I don’t know,” I said.

“They’d think we’re…we’re fucking missionaries.”

“I haven’t noticed any planes,” I said.

“Well, it’s still embarrassing.”

“I have given up on embarrassment,” I said. “At my age it is pointless. I am who I am. Let the pilots think we’re missionaries then.”

“We’re castaways!” Conrad said, as though asserting membership in some privileged class.

“Doesn’t it strike you as odd,” I asked, “that we are a thousand miles away from civilization, and you have brought with you to this place that one absurdity of living in a society. Self-consciousness? Embarrassment?”

Conrad didn’t hear me, though. He looked off in disgust. “What gives him the right? He just does whatever he wants. Without asking anyone. After all that shit about making decisions as a group. I knew it was all bullshit.”

“Just think of it as a couple of big sticks,” I said. “It doesn’t have to be a crucifix. It doesn’t have to mean anything.”

“It crosses the line,” Conrad said. “You know what it is? It’s state-sponsored religion. How does he know we all believe? How does he know some of us aren’t atheists? Or Jews? Or Hindus?”

Conrad, in his past life, was a labor lawyer or something. An advocate of some poorly-paid group, or class, or underclass. “You don’t look like a Hindu,” I told him.

“That’s stereotyping,” Conrad said.

I considered this, puzzled, but didn’t pursue it. “Maybe you should talk to him about it,” I said.

“Right in the middle of the camp!” Conrad exclaimed, still smarting. “That’s the problem. It’s like…government fucking property. He should have put it up somewhere else. In front of his shelter.”

From what I can tell, the Sovereign Nation of Illyria is about evenly divided between Republicans and Democrats, three of each with one independent—your humble chronicler. We have no social safety net, no taxes, a total lack of laws that would make a libertarian proud. On the other hand, our foreign policy is aimed at peaceful coexistence with our neighbors. And we consider ourselves to be pro-environment. For example, there is no peeing in Piss Brook. Strictly enforced. And we have started husbanding our excrement for the precious resource that it is, and putting it to use it in our farming experiments. You see how this place is the very inverse of our past life? Civilization in negative? Here our very stools—the quintessential waste product—are a measurable portion of our net worth.

It is remarkable how seamlessly our political disputes have moved from our former life into this one. Cole and Conrad still argue about tax policy, for example. And what to do with illegal immigrants. Although, should we die here, as I assume we will, it is unlikely any of this will ever matter again. You see the absurdity, the futility of these arguments we engage in? We have no problem of illegal immigration on Illyria. Nobody has shown up offering to do our laundry or to bag our groceries.

I find myself wondering: if a mutiny were to occur, with whom would my loyalty reside? True, I don’t like Cole. I don’t respect him. Only I don’t think Conrad would be a very good leader. Of course, Conrad and Cole are not the only two possibilities to lead us. There is Andreas—shy, handsome boy of twenty who had been the deckhand and cabin-boy on the yacht. He is bright and level-headed, from what I see, and the only one of us who does not appear to be suffering, who seems to see this as just an extension of his summer, a further break from college. What comforts does one need, after all, at age twenty?

Or perhaps we should try a matriarchal structure, like the Samoans had. Choose Gloria, chattering old lady, as our chieftain. Gloria is perhaps seventy, a widow, grandmother to a dozen grandchildren. She smiles when she speaks of them. The oldest is a lawyer with the Justice Department. The next oldest has a very high grade point average at Temple University. She had been knitting a sweater for her youngest grandchild when the boat went down, and somehow the wool made it onto the lifeboat. She washed it out and dried it and has continued with her project.

One night I am next to her by the fire as she holds the sweater up, imagines her grandchild inside it, considers the proportions.

“Very handsome,” I say.

“Yes,” she says. “Too bad he will never have it.”

“If you believe that,” I say, “then why continue with the sweater?”

“Well, I have to do something,” she says.

“Of course.”

“You have children? Grandchildren?” she asks.

“I have a son.”

She looks understandingly into my eyes, as though she knows what I feel. Only how could she know? “He must be suffering at losing you,” she says.

“I haven’t seen him in thirty-five years,” I say.

“Oh,” she says with a start, and politely changes the subject. “I think it must be harder on the young ones. I mean, we’ve had our time. Right?”

I have to admit I resent slightly Gloria’s intimations that we have something in common in our accumulated years. That we must share the same values. I must be as good, as upstanding, as resigned to death as she is. Gloria worked as a cafeteria lady in a local elementary school, was our cook on the yacht, and is our cook again on the island. She has a stocky stature, and I always imagine her in her white cafeteria uniform, arms folded under her shapeless, megalithic breasts, looking out over the children. The hairnet and sagging stockings, the cakes of flour-white make-up.

She has a slap-your-hands-together, let’s-get-down-to-business kind of spirit about her, is chipper in a way that I find unnervingly mindless, as though she is dealing with the seven-year-olds at her school, and—aside from some greater understanding of responsibility—is much at their level. I see her helping out on some field trip, there in the back of the bus, happily, even joyously, singing Ninety-nine bottles of beer on the wall with the children. I can safely say that nobody here on the island has warmed to her in a way that I imagine the singing children might have.

Has Gloria considered me as a possible object of romantic interest? Clearly, I am not capable of this, not merely because we have nothing particularly in common, but because my heart already belongs to another.

I have yet to say much of myself, so let me offer a few words here. I am a man in his eighties. My name is Hans. The hairs on my head have been reduced to a few scattered strands, sparse as the hairs on a coconut or the hairs on a testicle. I am a refugee, a wanderer, a retired refrigerator salesman, human organ dealer, warrior on the wrong side of history. I am in love with a nineteen-year-old girl. I am speaking, of course, of the aforementioned Dawn.

Dawn, Dawn, Dawn.

Dawn is Cole’s step-daughter. Of course, if the others knew my feelings for her they would be shocked. Or if they weren’t shocked, they would at least feel obliged to pretend to be shocked.

And yet it is true. I am in love with a nineteen-year-old child. And what of it? Why should such feelings be wrong in an eighty-five-year-old and not in a twenty-year-old? At what age does it become wrong to love? Wrong to yearn for youthful beauty? Or do you doubt that I am capable? Let me say that I have been assured by professionals, by those who should know, that I have the genitalia of a much younger man. My erection is as firm as a senator’s handshake. So should I not endeavor to contribute my genes to our little colony before I expire? Should our gene pool include only those offspring of our alpha male, as though we were a troupe of gibbons? Do we really want five Cole juniors for the next generation, five male models, admiring themselves in the reflection in the cove, wondering who is the fairest of them all? Or worse still, all vying to be the leader, dividing up the island, buying and selling their beachfront real estate?

I did not choose this predicament. I am sleeping just a few feet away from a beautiful nineteen-year-old girl. Am I not still a man?

It was not supposed to end like this, with us huddled together on a beach somewhere, wondering who is going to die first. How did I find myself on this excursion, after those years ensconced, alone, in my villa by the sea? I was living the life of a recluse, an old salt, an old masturbator, when one morning, on a day just like any other….

Scratch that. I am not ready to tell about that. We will get there. In due time. But now I see I must go back further. I must say something more of myself.

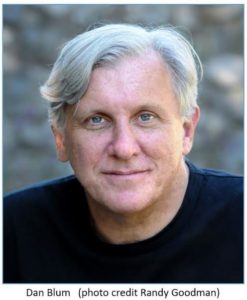

Daniel A. Blum grew up in New York, attended Brandeis University and currently lives outside of Boston with his family. His first novel Lisa33 was published by Viking in 2003. He has been featured in Poets and Writers magazine, Publisher’s Weekly and most recently, interviewed in Psychology Today.

Daniel writes a humor blog, The Rotting Post, that has developed a loyal following.